PAOLA TORRES NUNEZ DEL PRADO: THE CITY OF EARTH TEMPLES

CODDIWOMPLE

SECRET CORNERS

Tales on favourite spots by our network of femxle musicians

PAOLA TORRES NUNEZ DEL PRADO

THE CITY OF EARTH TEMPLES

When I was around the age that my child is now, my uncle used to take us for walks to the sandy areas of CIENEGUILLA, a rural area in the outskirts of LIMA, the city I was born and grew up in. There we would walk through those desertic esplanades surrounded by arid hills, which should have protected the remains of the pre-Columbian tombs buried there but didn’t, as those treasures laid scattered over the terrain like a puzzle that will never be fully solved.

I remember picking up pieces of reddish ceramics in excitement, which I found by noticing their tips peeking out from their former burial. I would look further under the stones then, thinking that perhaps they belonged to some ancient lithic structures now destroyed. Then I got so excited about the possibility of accessing a story that no one could tell me, but that I, with the freedom that my young age allowed me to have, could witness directly and reconstruct without restrain nor responsibility, free from the institutional intermediary who tends to cage historical objects for untouchable exhibition and conservation. I was free to imagine what I pleased when I grabbed those fragile pieces thinking about the people who made them; people who looked like us but who left traces of an existence that was very different from ours.

The murmur of the air brushing my eardrums has been left inscribed in my mind; that same wind that blew dust and the dry mats of hair that laid scattered in the area, although it did not move the bones resting just next to them because they were still very heavy. It is clear to me now that this entire area had been so intensely looted, or as we call it, HUAQUEDA that by then it was difficult to know what happened there centuries ago, although I would dare to say that those were the miserable remains of the mummies that the HUAQUEROS – those looters who unearth the graves to sell what they find to private collectors – had no interest in taking along. Thus, all that landscape had ended up spotted with whitish bones and tangled clumps of black hairs like patches partially covering the desert, organic wigs that we also grabbed and dropped with a mixture of disgust and desire, because it was then that we really touched those beings of the past; our ancestors, our extended family, ourselves from other times.

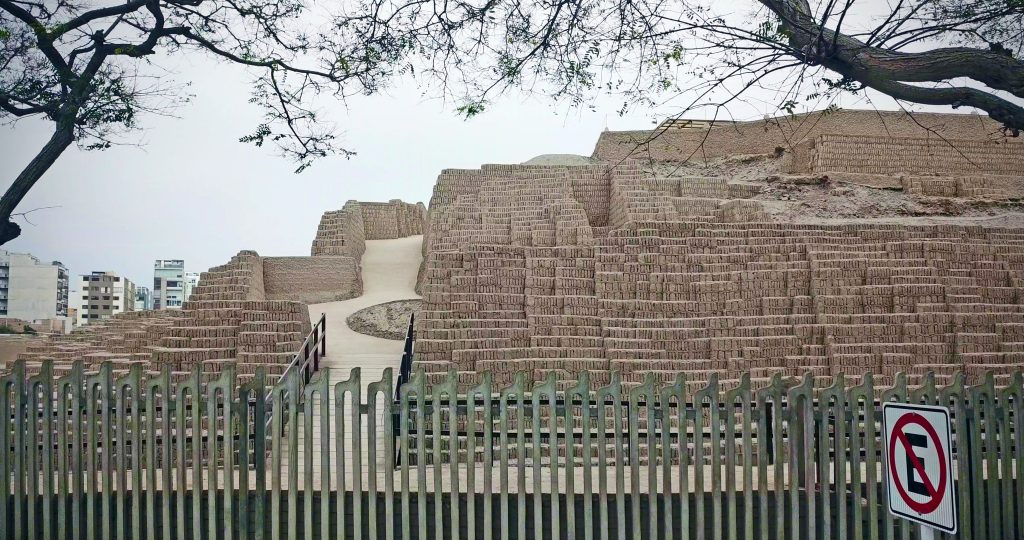

Lima is a desert city made up of mostly cement neighbourhoods that, just as the black mats of hair that contrasted against the uniformly beige landscape of Cieneguilla, are disrupted by patches of earth temples that we call HUACAS: the original Quechua term from which the hispanized words huaqueros and huaqueados, mentioned above, sprout from. There are Huacas in the northern parts of the city, and in the southern parts too; there are Huacas towards the East; there are important sanctuaries like PACHACAMAC in its outskirts, and, not that far away from the metropolis itself, the oldest Huaca, the CARAL COMPLEX, the most ancient temple of the whole Americas. These structures seem to be rather bothersome for the grey expansion of the city itself: usually enclosed within walls or rusty metal bars, they appear to have been constricted to the smallest possible area, in the case they have survived the invasions of surrounding neighbourhoods that is, or from nearby companies that have taken them down without second thought to allow their own growth.

Truth is, in Peru there is something that people sometimes call “the damnation of the National Institute of Culture” which is related to the fact that, if archaeological valuables are found in areas owned by a person or a company, the State has the right to claim the area in order to safeguard the objects. This, of course, is not a good thing when you have paid for a certain land. It is simply bad business. Hence the viewing of such events as a curse. Many opt not to say a thing or to pay off whoever knows about the findings so not to lose more money otherwise. Yet, I have always wondered how no one has given any serious thought on what a good touristic business would be if Lima would be presented as “The City of Earth Temples.”

Oh well, enough of giving value based on how much income something can bring or not, I say! These places still talk about their origins and ours, I assure you! As they have shared stories with me since I have been a child, in the moments in which I passed next to them and wondered about who made them, just as I did when walking in Cieneguilla, when the wind blew and stole particles of their dried-up adobe walls that ended up in my face and entered my nostrils so I could even smell them, and, in the city, when they finally opened the doors to allow me to step over them, for then to be able to see a mummy or two, sharing my emotions with the person taking care of the small museum that they tend to have if properly preserved, who finally allowed me to cherish and enjoy the earth temples that so many wish would lay forever underground.

Nowadays, I try to harness the remembrance of such whispers from both the past and my past, materializing them in rendered structures or into sound again. This is how, around a year ago, while recording some visuals of these Huacas with the drone, an old woman living in one of the adjacent houses got evidently uncomfortable with our presence. She finally shouted at us:

“Hey! Hey, you! What are you doing there, huh?”

Puzzled, we simply answered that we were filming the temples.

“What?” she said, “And who is going to believe that? Who would want to film those disgusting ruins! Come on… Do not try to fool me! Just go away!”

And then she proceeded to call the guards on us. They immediately came, and asked what were we doing. We simply explained that we were shooting with the drone, and that it was all within what was permitted, according to law. The woman continued screaming, this time because of their incompetence out of not taking us away immediately, even if they tried to explain to her that we were artists, and that these were archaeological remnants that many tourists did appreciate…

“Shut up! No one cares for those old things! NO ONE!”

As Peruvians, sometimes it seems that we are only the leftovers of what once was a legendary Empire, and that we lay now in some sort of limbo in between a mediocre modernity and a great past. And that past is the image that we, with great effort, (re) build and export to a globalised exterior, maybe to have more potential tourists interested in visiting us, hoping to find a niche for our unique status, where we sadly are rarely seen as innovators, discoverers, or inventors, and, if so, with the tendency to fall within a framework that could be considered exotic when that cultural legacy – that of before but not now – is commonly referenced.

The truth is that there is no adequate terminology yet to classify these lands and their people, us, who are not part of the Eastern world either; not being entirely “ancestral”, nor really an example of an industrially and technologically advanced society, it is this indeterminate state that makes obtaining a name to define ourselves in a titanic task and leaves us only with that word that ignores the indigenous presence and their languages: Latin America, the land of adventure, sensuality, parties and buried secrets, where even a virtual Indiana Jones came to “safeguard” the pre-Hispanic treasures that are still hidden in this area of dubious borders.

Although there is the possibility of radically claiming that cultural heritage, referencing that indigenous past in an open way as part of our identity, it is also true that it could expose us to accusations from an Academy that could brand us as cultural appropriators (with the negative charge that it brings) in case our families did not keep the traditions of their ancestors or remain ethnically “pure”. Or even worse: we can be seen as “self-exoticizing” ourselves, in that case, blaming us for putting in practice a very strange self-exploiting technique that would fulfill the role that is expected from us, in a strategy that would finally allow us to attain economic gain from such self-exploitation, or recognition, or who knows what.

I think that, simply, it is not fully understood that we are in the process of defining who we are and where we belong: if we are closer to those who colonized these lands, or if we are the descendants of those who fell victim to the external powers… Either way, we are always being externally pushed into a binary scheme that really does not apply to our condition, that, in a way, ends up like the arid plains of Cieneguilla, a few kilometers away. With the big city, with its modern automobiles and its financial centers with reflective windows; closer still, the precarious houses of human settlements, where people survive as best they can, while, in the arid soil more in the distance, that puzzle continues to lay scattered without assembly, whose pieces us artists and musicians keep on collecting so to creatively reassemble them, filling the missing gaps with what we dream of while putting them together again.

Paola Torres Núñez del Prado (PE) explores the boundaries and connections in between tactility, the visual and audio related to the human voice, to nature, and to synthetic ones, those whose listening is often considered less harmonious, such as machine or digital noises.

Her work is essentially complex: she explores the limits of the senses, examining the concepts of interpretation, translation and misrepresentation, so to reflect on mediated sensorial experiences while questioning the cultural hegemony within the history of Technology and the Arts.

Her performances and her artworks, which are also part of the collections of Malmo Art Museum and the Public Art Agency of Sweden, have been presented in diverse countries of the Americas, Central Europe, and Scandinavia, where she is currently based.