CARLA VITANTONIO: ARIRANG – NORTH KOREA’S MASS GAMES

ZUIHITSU

QUIRKY THOUGHTS COLLECTION

Essays, personal stories and curiosities from our guest femxle contributors

CARLA VITANTONIO

ARIRANG – NORTH KOREA’S MASS GAMES

AN EXCERPT TRANSLATED FROM THE MEMOIR “PYONGYANG BLUES” BY CARLA VITANTONIO

COURTESY OF ADD EDITORE

(HUGE THANKS TO ILARIA BENINI FOR MAKING THIS POSSIBLE)

Back in high school the Epic class was my favorite. It was held every Wednesday morning, from 8.30 to 10:30 am. We studied how the Greeks first and then the Romans depicted themselves and recounted their stories. I particularly loved to hear about how Epic had started: through the narration of incredible adventures of kings, warriors, gods and heroes by storytellers describing the society and placing every single person in their rightful places in the world. Thanks to Epic poems everyone knew what to do, what dress to wear, even what kind of language to speak.

I liked Epic so much that growing up I became a storyteller too, describing what I cared about and what I felt I could portray, hoping to be able like the aoidos of the past to advise people on how to dress, that is to say a little better.

Epic plays a key role in North Korea’s self narration. After the Second World War, Korea was abruptly divided in two parts, each subject to the protection of one of the two victorious powers (U.S.A. and U.S.S.R.), and it was necessary to rebuild a new collective consciousness from scratch.

With the support of the Soviet comrades, the North Korean regime, in a much more far-sighted way than the South Korean one, made a commitment as early as 1945 to create a narrative that had all the components necessary to satisfy the intimate needs of the people.

A strong and charismatic leader who, with very few comrades, rises up as a new David against the Japanese Goliath; a sacred place, beautiful and difficult to reach, identified as for the Greeks in a very high mountain (1) ; a country to be liberated; an unbalanced and arduous struggle to lead; a proud, generous, revolutionary people who first got rid of the Japanese yoke and then of the American one.

The regime engaged in such a coherent, massive and flawless way in the dissemination of this narrative that to discern exactly the real from the myth is a complex undertaking with uncertain results.

Not completely satisfied with the result, leader Kim Jong Il, known for his meticulous attention to mass media and in particular to cinema, invented a new and spectacular means of disseminating the National Epic in 2002: the Arirang.

Arirang is commonly called a mass game, but it is much more.

It lasts almost two months and takes place in the Arirang stadium, a gigantic flower-shaped building on the road leading to the university.

Joining the Arirang dance troupe is an honor for every Korean. Artists of all ages are selected for the Arirang based on a series of criteria including physical prowess but, in accordance with the Juche doctrine, most of them don’t do this for a living.

During my first year as an Italian teacher in Pyongyang, my students were chosen to be part of the Arirang scene where Korea gets rid of the Japanese.

While other schoolmates devoted themselves to the restoration work of the university, they were recruited full-time for three months in choir rehearsals that lasted hours. The youngest children were five years old and they performed in tedious and exhausting numbers such as: the children and the future, the growing country, the children who are happy, the children who have nothing to envy any child from any other country in the world.

Every year until 2013, when it was suspended until a later date, the Arirang retraced the true and mythicized history of the country, from the birth of t’aekwŏndo (the traditional martial art that is practiced in a slightly different form in North and South Korea), up to present times, and clearly stated who were friends and foes. For example there was a whole piece about the Russian friends, who were unsurprisingly involved in a major restoration work on the national railways at the time.

It is not easy for a Korean to have access to Arirang. As in everything, you have to be chosen.

Every day, for two months, dozens and dozens of buses offload dressed-up citizens in front of the stadium. They come from all over, having traveled for hours and sometimes days because they had been given the privilege of attending the show.

And then there is a VIP sector, reserved for the authorities and the paying public, namely us: the foreigners. Not so much and not just the foreign nationals living in Korea, but rather the several hundreds of tourists who flock to the country every year on this occasion thanks to three authorized travel agencies.

A ticket to Arirang costs about eighty euros. My first year in Pyongyang I had bought the full price ticket, I went to see the show and a week later I received an invitation from the Foreign Ministry to attend the show together with the diplomatic delegations.

Great timing.

When I paid for the full price ticket, I was seated on a plastic stadium seat, separated only by a thin iron bar from the overflowing and enthusiastic local population carrying plenty of colorful fizzy drinks, snacks of all kinds, dry fish supplies and bottles of water. But when I was invited, I was seated on the padded seats rows, located a little higher so that people could turn around and look up to me. Well, not me specifically, but what I represent: a foreign country that pays attention to this country’s self narration.

Tourists are always in the cheap seats and are usually dressed very badly. They wear shorts, sleeveless tank tops, sandals with broken buckles and fanny packs.

Every time I see them I keep thinking that they have never been told of how inappropriate those pieces of clothing are – neither here nor in any country on this continent, excluding perhaps the hyper-touristy islands in Thailand.

I’m bothered by such tourists who behave as if they were in their own backyard, and probably would not realize the differences if they were suddenly transported to Italy, Cuba, Russia or South Korea. These buffoons and posers, who will add a star to Pyongyang on their Tripadvisor’s world map tomorrow, make me feel uncomfortable. I’m embarrassed for them.

I’d like to apologize to all the seventy-year-old ladies who carefully bathed after having carried home buckets of cold water distributed by the tanker, who ironed their best dress and wore it with dignity despite the 35 degrees, and to the soldiers with their uniform stuck on their back. I’d like to apologize on behalf of these tourists who don’t question themselves and don’t realize that they are embarrassing us.

On these occasions, I keep hoping not to meet any Italian tourists to be ashamed of, since Italian is my mother tongue.

People living in Pyongyang all wear the glad rags, and even our personal Korean (2) usually dresses up, in order to pay tribute to the country (them – the locals) and to the artists (us – the foreign residents).

After all my years of broken theatre where crusty punks throw up during the shows, drunk people interrupt and people too often wear baggy pants, I personally always dress up when I go to see a show.

I dress very well, better than ever. I even put on stiletto heels, although I know that the only one to see them is my personal Korean during the slow parade from the car to the seats.

Arirang is beautiful.

I know I’m unpopular when I say it, and that’s why I have stopped saying that to my expat friends, but I don’t have any feelings of pity or outrage for the tens of thousands of performers who move in unison throughout the narration. Not even for the children. I can’t honestly say what I would have done to be part of a contraption like the Arirang as a child while I was just a lousy chorus girl in a small town dance school.

Arirang is wonderful.

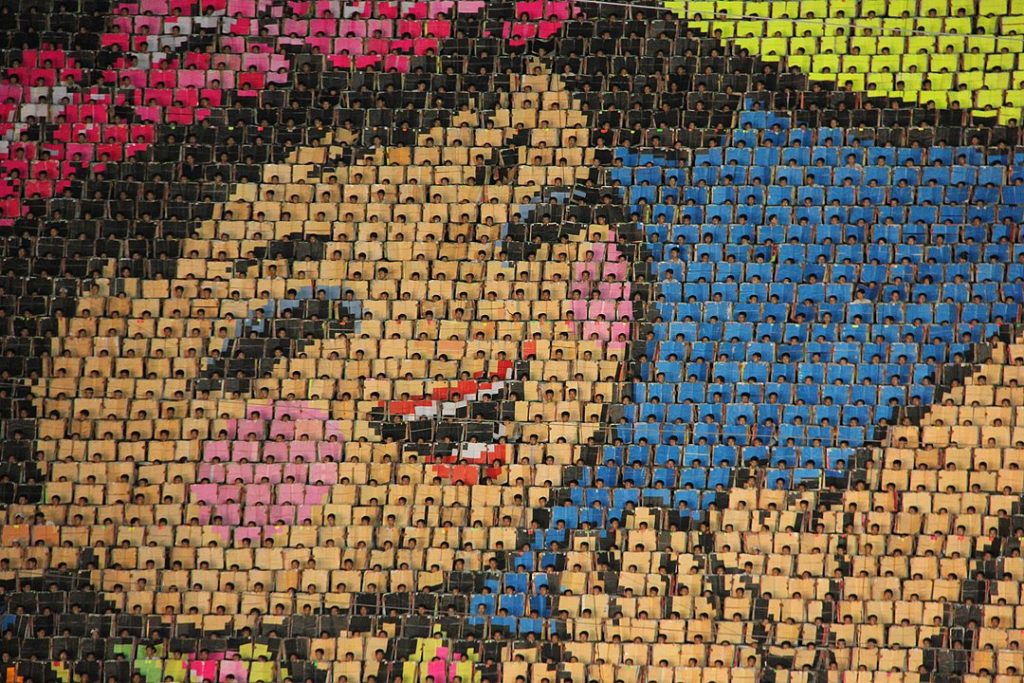

Not only Arirang tells us what this country thinks of itself but it also shows us how effective this regime is.

In my opinion, the thing that really bothers all of us is that we know too well that with sheer coercion the regime would not have been able to get all these people to undergo draining rehearsals under the sun every year for months and months. With sheer coercion, the regime could not have pushed the old peasant women with their ch’imachŏgori (3) onto second-hand buses.

What we see during the Arirang that makes us gnaw at and makes us point the finger at children, at the inhuman perfection of human decorations in the background, at the acrobatics and the patriotic music, is the fact that they believe in it. The regime’s big miracle is having been able to convince a good part of its citizens that this is not a myth, this is history.

Arirang shows it to us, casually rubbing it in our faces. This is what really gets us and what we can’t come to terms with, because we have never experienced the happiness, dedication and devotion that these thousands of people show.

This gigantic, carnivorous, cannibal concrete flower feeds on hundreds of thousands of children every year to the dumbfounded amazement of the world.

What we witness during Arirang is not part of our world and it represents values that we are not familiar with, therefore we’re lost. We don’t have any point of reference. We can’t explain it.

Obviously I refrain myself from saying these things; I only think about them because if I did say them, I would be publicly lynched in the Friendship ballroom, the multipurpose restaurant located in the centre of the diplomatic village where we – foreign residents – spend a lot of our free time.

The point is that we are so ideologically terrified by this country that making a clear analysis is not possible. If I were to say what I think, I would be accused of being pro regime. Nobody would think: “Oh, she’s trying to make a clear socio-political analysis”. It could never happen.

Regarding this country, people are for it or against it. And we have to be against it. We have to be against it 100% because only if we’re against it are we granted access to our community, the free world community (they say) and the capitalist community (I whisper).

It is so scary that we can’t afford the risk of accepting a part of it, of having a critical stance. We simply can’t. They are the bad guys. We are the good guys.

That’s why during the Arirang we eat dirt and can’t enjoy the show.

(1) Mount Paektu, a volcano located on the border with China, where it is said that Kim Il Song had his secret base during the war and Kim Jong Il was born.

(2) Every expat residing in Korea has one. It is a person appointed by the Foreign Ministry, who has the task of checking that the expatriate entrusted to him does not break the rules.

(3) In North Korea the traditional Korean dress is called ch’imachŏgori, which means more or less “skirt and shirt”. In South Korea it is called hanbok. The North Korean language rejects any word constructed with the prefix han, as it implicitly refers to the division of Korea after World War II and the supposed primacy of South Korea.

Mass Games in North Korea – Arirang

Carla Vitantonio is a humanitarian worker and a performer. After having spent 4 years in North Korea and 2 in Myanmar as head of mission for an international NGO, today she works in Cuba. Meanwhile, she performs her monologues in theatres, clubs, radio-stations all over the world.

Pyongyang blues is her first book in a trilogy in progress – published by Add Editore (Italy) – focusing on humanitarian aid in Socialist countries.