ECKA MORDECAI: ON BODIES AND EGGS

ZUIHITSU

QUIRKY THOUGHTS COLLECTION

Essays, personal stories and curiosities from our guest fem人le contributors

ECKA MORDECAI: ON BODIES AND EGGS

There are so many things I want to tell you. Things felt and known by my body, yet it’s hard to tell you in written language of listening and feeling and touching and smelling.

Take an egg and pierce the shell.

Pick away fragments to make a hole.

Empty the insides by sucking or blowing.

Clean the eggshell by rinsing and boiling.

Dry, then blow into the hole.

~how to make an egg flute

I wanted to tell you about egg flutes, but my failure to articulate exactly what they are has stunted me, led me to evade them. Loosening my tongue I’m giving them space, now, to breathe, to exist not as things but as the consequence of what I do in practice, in my daily life.

Sometimes I claim to make them without thinking, but this insults thinkings done peripherally: in my body, my senses, in the absence of words. Thinking is felt, and feeling is improvised so to understand why someone would make an egg flute, one must first understand why that person does anything.

I do things: make sounds, sense temperature, throw driftwood to flames and inhale scent by fire. I wake up and want to put liquids in my mouth, or, if there is a beautiful landscape I wake up and walk without direction, sometimes until delirious.

I follow my feelings, those internal maps hold keys for decision-making. Affected, I retreat inward, allowing feelings to take shape I turn them over in my mind’s palm. Weighing up options, I’m led by pleasure and if my body feels weak, I eat an egg.

I’ll tell you how I made the first egg flute.

I went to visit the neighbour’s chickens, not my neighbours but the farmhouse next to Mhor Farr, a remote residency space in the Scottish Highlands led by artist-facilitator Fionn Duffy.

The neighbours had an honesty shop outside their house made from a rusty unplugged fridge with ‘EGGS’ painted on the front. I opened the door and inside found a dozen in blue and ivory, piled against a grubby white interior. I was used to seeing farm produce nestled in hay but these eggs, on

plastic, spoke differently. They told me nothing of where they came from, they didn’t need to. They told me only that they existed, and that they were mine.

Take as many as you can carry

In your hands or pockets

~how to gather eggs or potatoes

An egg in the hand is affirming because it is palm-sized. With my two palms and fingers I folded the hem of my jumper to my chest, creating a pocket.

In exchange for some coins I carefully took twelve eggs, crossed the lane, back to the studio where I observed the eggs, eventually emptying them.

The insides smelled like transparent bodies, eerily young and lactic.

My first idea was to paint scores onto them because as a child in Wales I used to paint egg-shaped stones, leaving them as gifts along the beach, but I couldn’t stop thinking about my mouth and blowing. Of breath and bodies and mouths and blowing and that’s when I noticed I’d made a flute.

Breath

That evening an octet performed the egg flutes.

I’d prepared the scene in a ritual manner: around a large round table each place had a straw mat, a handwritten score, a dram of whisky, a small pile of salt, a painted half-eggshell, and an egg flute.

Everyone was giggling. I don’t remember why, but I’d taken us on a silent walk of the garden in pitch-black darkness before leading the group to the table. I must have convinced myself it was an act of ‘resetting the ears’ or ‘focussing our listening’ but in hindsight that was foolish.

The ears are already set in chaotic, continuous channels of motion and the challenge of a listener is to accept this, to submit, not to refresh.

Some say that eggs, too, are a symbol of continuity.

Mythologies of cosmic eggs are found throughout the world hatching birds, reptiles, humans and deities.

In ancient Egypt an octet of frog and serpent-headed deities known as the Ogdoad created an egg from dark, watery, unknown “nothingness”. This egg birthed the sun-god Ra, as well as the the world’s first primeval mound, or land mass. In other versions of the myth, the egg is laid by a goose named “the Great Cackler”.

The Chinese myth of Pangu uses a big black egg as an analogy for universal chaos. Pangu sleeps in the egg for 18,000 years, then hatches, splitting the universe into Yin and Yang by precisely ten feet per day. After a further 18,000 years, Pangu dies, and the parasites on his body become human.

At my primary school, chickens were a regular feature of childish conversation. That witty quip of “which came first…the chicken or the egg?” tells me that we’d already found a way to contemplate complex philosophical concerns.

Back when I made egg flutes to sell, I encountered a clutch of eggs with lumpy clusters emerging from the outer shells. I was repulsed, as though the eggs were taken by malignant growths, and began to imagine alien worlds in which eggs reproduced rhizomatically. I researched mycelia and slime mould and the way humans have mimicked them to create networks of communication: namely Tokyo’s rail network, and the internet.

It turns out these clusters were just calcium deposits, but by this point I’d accepted The Egg Came Before The Egg.

For an egg to be Kosher, it must have been laid.

In 2014 Rabbi Josh Strulowitz discussed the unique status of eggs in Halacha (Jewish law) stating that an egg is Pareve (neutral, neither meat nor dairy) only once it’s left the chicken, and that if one were to find an egg inside a chicken, it would be classified meat (fleishig).

In this model, the chicken comes before the egg, and the egg itself is a chicken before it is an egg.

In all my research on the relationship between humans and eggs, however, I’m yet to discover another egg flute.

There’s examples of egg shaped flutes such as the Chinese Xun and Italian Ocarina but these are formed from clay, not real eggshell.

Perhaps I’ve not searched deeply enough, or maybe they’ve been written out of history due to their fragile, feminine or folk connotations. It could even be that no-one liked the sound of them; though I find that hard to believe, with their beautifully hollow and brittle lament.

So despite my struggle to describe them as things in themselves, I continue to make these egg flutes, ponder them, turn them in my mind’s palm and my actual palm as a practice, as a thing I do in my daily life.

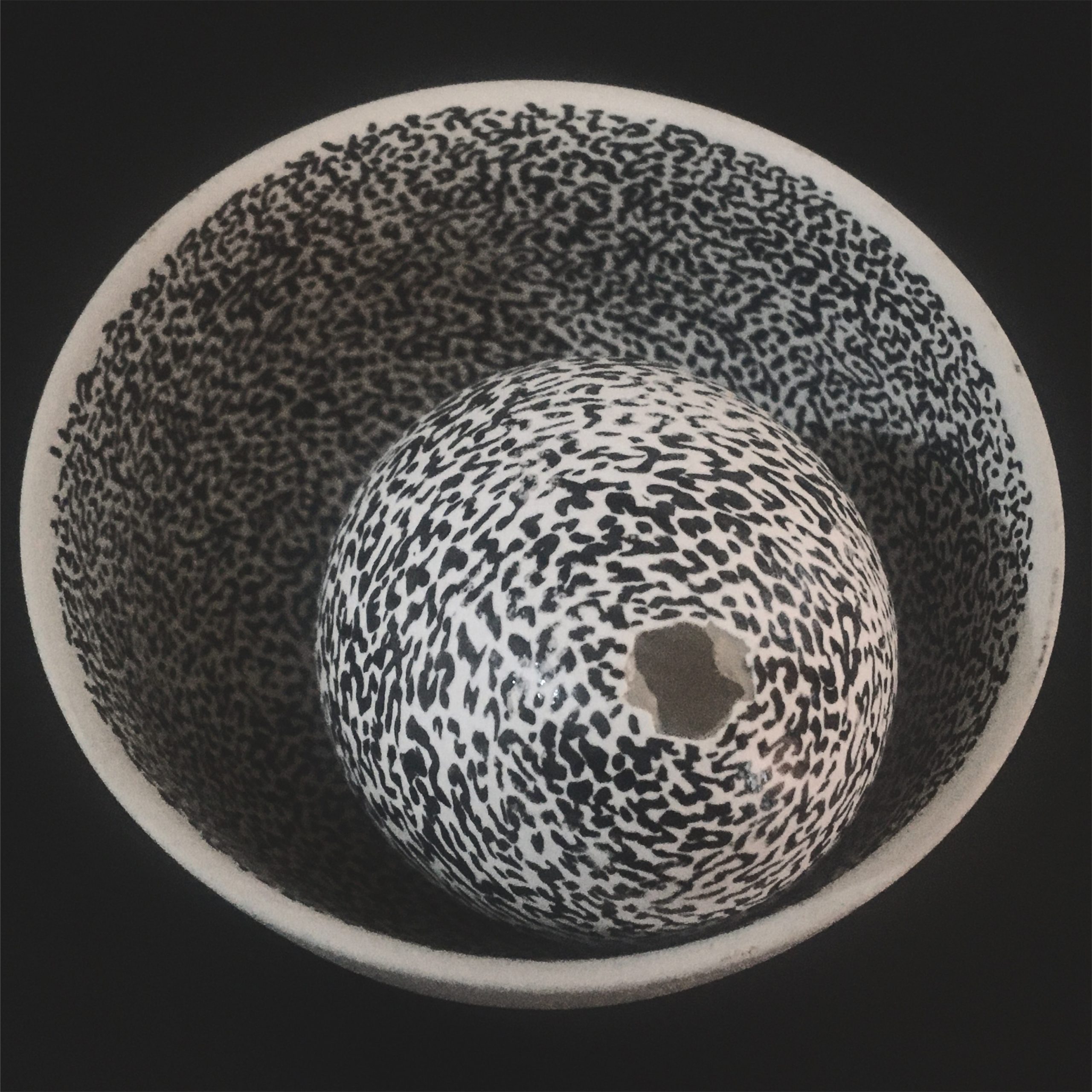

Pic by Jaime Caranzza

Ecka Mordecai is a‘cellist. Experimenting with performance, voice and body, she’s collaborated with Andrew Chalk and Tom Scott (CIRCÆA), Valerio Tricoli, Lia Mazarri, and worked with David Toop + Rie Nakajima, Clive Bell, Vanishing, and Thurston Moore. Solo and group shows include Cafe Oto, Hepworth Gallery, Speicher II, and Christian Marclay’s ‘Liquids’ at White Cube, performing scores by Yoko Ono and George Maciunas.She was taught ‘cello, viola da gamba and renaissance music for a few years at high school, followed by studies in performance and sound art , alongside self-developed cello playing. An active participant in community arts collectives, Ecka’s past residencies include Islington Mill (Manchester), Nutclough Tavern (Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire) and Mhor Farr (Wester Ross, Scotland.