JULIA KENT: MAX NEUHAUS

ZUIHITSU

QUIRKY THOUGHTS COLLECTION

Essays, personal stories and curiosities from our guest femxle contributors

JULIA KENT: MAX NEUHAUS

Pioneering sound artist Max Neuhaus was born in Beaumont, Texas, in 1939. He played drums from early childhood, aiming to become “the best drummer in the world.” He studied jazz drumming with Gene Krupa and Samuel “Sticks” Evans, and, in his teens, started his own band, the Blue Notes Orchestra. His parents insisted he go to college, so he enrolled at Manhattan School of Music, practicing relentlessly and developing a formidable technique. After graduating he became celebrated as a virtuoso interpreter of contemporary works for solo percussion. He toured with Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez, performing and traveling with over a thousand kilos of instruments and equipment. Setting it up and breaking it down was so onerous that composer Philip Corner created a work called Everything Max Has, which turned the process into a performance. “Max always complained about not getting to the after-concert parties,” Corner said. “So I made it so he could.”

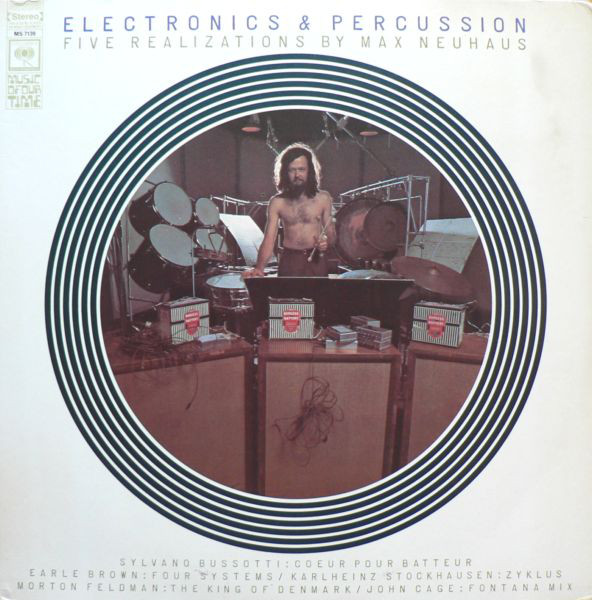

In 1968 Neuhaus released an ambitious solo record for Columbia, ELECRONICS AND PERCUSSION: FIVE REALIZATIONS BY MAX NEUHAUS, which featured works by Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, Sylvano Bussotti, Stockhausen, and John Cage. They were notated graphically, and granted agency to the performer through indeterminacy and improvisation. As the title of the record suggests, Neuhaus went beyond simply interpreting the scores. For the Cage piece, Fontana Mix, he used an electronic circuit he had designed, the Max-Feed, to manipulate feedback from contact mics on his timpani, creating a new piece he called Fontana Mix-Feed, a series of drones and vibrations, visceral and unearthly, that still sounds startlingly innovative. Every performance was different, depending on the shape of the performance space and the configuration of the audience.

In the late 1960s Neuhaus moved away from the linearity of performance and began to create sound installations, exploring how sound could define space. He wrote: “Traditionally, composers have located the elements of a composition in time. One idea which I am interested in is locating them, instead, in space and letting the listener place them in his own time.”

He created works for telephone networks, fans on roofs, penny whistles in a swimming pool (requiring listeners to put on bathing suits and enter the water), and radios in trees transmitting sounds to be heard by passing cars.

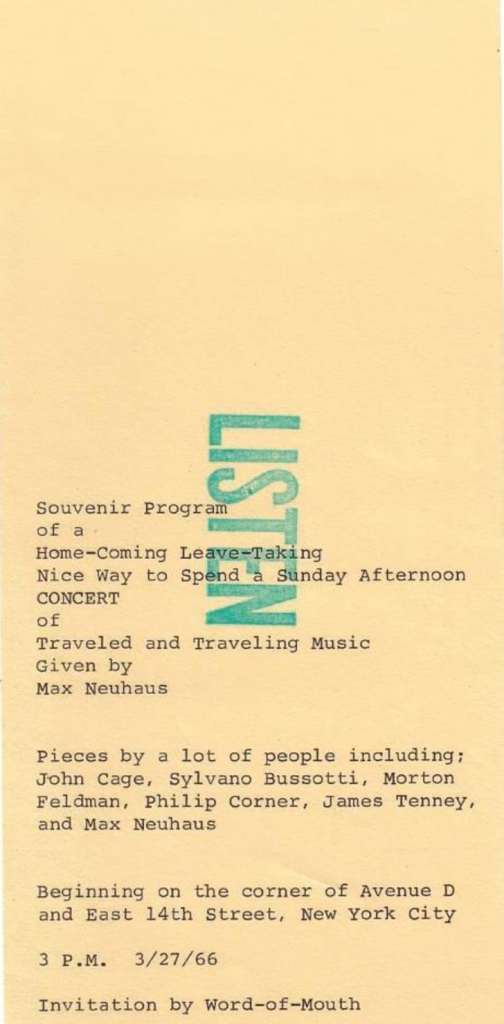

One of his earliest works, LISTEN, was a sound walk he led in the East Village, around 14th Street and Avenue D, across from a hulking and ancient power plant that dominates the neighbourhood (and plunges it into darkness when it fails). He called it a “concert of traveled and traveling music.” He stamped the audience’s hands with the word LISTEN, and led them through the streets, listening to the sounds of the power plant and traffic and the urban environment, then brought them to his nearby studio to hear a solo percussion performance. Other artists, like Christine Sun Kim, have traced the path of this ground-breaking work. Kim created a sound walk in 2016 (the 50th anniversary of Neuhaus’s) that focused on her own and her audience’s memories of the neighbourhood, creating a mnemonic throughline on East Village streets that have been radically transformed through gentrification and development.

Neuhaus called his subsequent sound walks “Lecture Demonstrations.” He continued to stamp the audience’s hands with the word LISTEN. “The rubber stamp was the lecture, and the walk was the demonstration“, he said. By inviting the students at his lecture at a midwestern university to leave the hall and participate in a sound walk, he derailed his academic career. “The faculty was so enraged that, to a man, they boycotted the elaborate lunch they had prepared for me,” he wrote. “The Iowa experience…blacklisted me as university lecturer.”

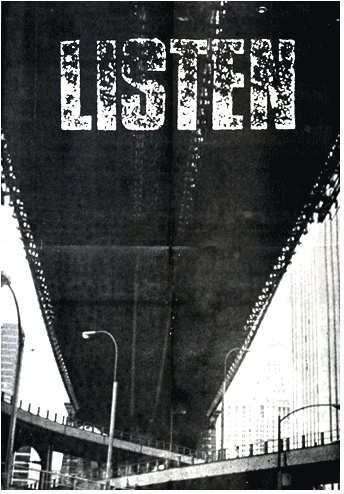

As part of the Listen project he wrote an op-ed for the New York Times responding to a pamphlet written by the Department of Air Resources about “noise pollution” in the city. He also made a visual artwork, a photo of the underside of the Brooklyn Bridge, with the word LISTEN stamped over it. “This idea came from a long fascination of mine with sounds of traffic moving across that bridge,” he said, “the rich sound texture formed from hundreds of tires rolling over the open grating of the road-bed—each with a different speed and tread.”

He created an alarm clock that woke the sleeper with silence (it emitted white noise at increasing volume and then stopped at the wake-up time) and worked on a project to redesign the sound of emergency sirens to make them more locatable and less alarming: “to have authority without being authoritarian“, he said.

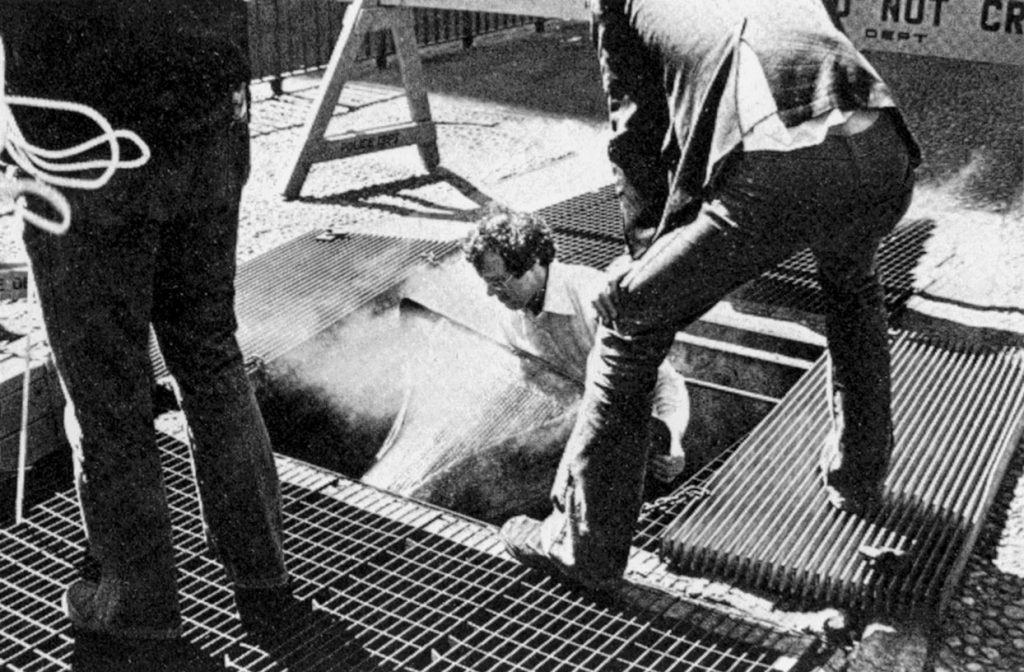

Perhaps his most famous (or most-visited) work is TIMES SQUARE. After tortuous negotiations with New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority, he finally succeeded in getting permission to install, under a grating on Broadway between 45th and 46th Streets, sound generators of his own design, and an amplifier. He couldn’t use power from the subway, as the voltage was too high, so he connected them to a streetlamp: a uniquely New York City solution. Times Square created sound from 1977, when it was installed, until the early 1990s. Periodically, transit workers would disconnect the power, and Neuhaus would have to reconnect it. “So every six months or so, he would appear in hard hat and overalls, carrying a tool kit and traffic cones, and get it going again,” the Times reported (“Max Neuhaus’s ‘Sound Works’ Listen to Surroundings: Been There, Heard That,” New York Times, 17 November 1999).

Once he began spending more time in Europe, he continued to monitor the work with a webcam, but it fell into disrepair.

In 2002 the Dia Art Foundation, whose Dia:Beacon satellite hosts Time Piece Beacon, another Neuhaus sound work, restored it. Neuhaus described the sound it creates as like “the after-ring of large bells.” It’s a meditative sound, a deep, harmonic, complex drone that music critic John Rockwell described as “like a rich organ chord…surprising and consoling.” To me it sounds like a responsive vibration that never ends, abstracting the energy of the city into something enveloping and moving and beautiful, as though this overwhelming and transitory urban space is embracing you with sound and making time stop.

The work is unmarked, meant to be discovered rather than labeled. “People, having no way of knowing that it has been deliberately made,” Neuhaus wrote, “usually claim the work as a place of their own discovering” (“Art Form’s Pioneer; Achievers’ Incubator,” New York Times, 19 February 2010).

Since Neuhaus installed his piece in the ’70s, Times Square has evolved from gritty, gaudy porno hub to Disney-fied tourist attraction, a synecdoche of New York City, where nothing stays the same, and money flattens the contours of individuality into a smooth, quantifiable curve. During the pandemic Times Square was eerily quiet. But also, for a moment, there was a chance to pause in the heart of Manhattan and feel the ghosts of all the dreams that have passed through. Now the tourists and the franchised hustlers—the Naked Cowboy, the grimy Elmo, the limp-eared Minnie Mouse—are back. And Neuhaus’s sound still resonates, creating its own aural space in the chaos of the city, bringing eternity to Times Square.

Canadian-born, New York City-based cellist and composer Julia Kent creates music using layered and processed cello, electronics, and found sounds. She has released five solo records, the most recent being Temporal on UK label Leaf, and has toured throughout North America and Europe. She also composes music for film, theatre, and dance.