DIANA LOLA POSANI: SCREAM AS IF YOUR ORGANS WERE MADE OF GLASS

ZUIHITSU

QUIRKY THOUGHTS COLLECTION

Essays, personal stories and curiosities from our guest fem人le contributors

DIANA LOLA POSANI: SCREAM AS IF YOUR ORGANS WERE MADE OF GLASS

One day in 1840, Princess Alexandra Amelie of Bavaria was found walking sideways through the corridors of the palace.

She was already known to be an incredibly intelligent girl, but with a particular sensitivity: she dressed only in white, and could not stand many colours and smells. When family members asked her the reason for her behaviour, she was forced to explain that she had suddenly realised that she had swallowed a glass grand piano as a child. The piano was now laying completely intact inside her, and could shatter into a thousand pieces if she was to be harmed or moved around.

She was a victim of the Glass Delusion, a collective psychosis that was widespread from the Middle Ages until the end of the 19th century and that made people think they were made of glass.

In “An Odd Kind of Melancholy: reflections on the glass delusion in Europe”, Gill Speak describes its various forms: sometimes people became lamps, sometimes urinals, other unfortunates found themselves trapped in a glass bottle. The reasons behind the fear of breaking were hinted at by Gill Speak as chastity, purity, and luck.

Psychiatrists regarded the fear of breaking as a particularly imaginative form of melancholia. And melancholia is very often connected with illusions, as Speak wrote.

The last officially recorded case is an anonymous woman from an asylum in Meerenberg, who convinced herself of being a bottle shard not long ago.

Reading it made me wonder what a bottle shard could be afraid of; in this case the terrifying prospect had already been resolved and she had already broken.

Perhaps there is relief in being beyond impact?

Around the same time of the Glass Delusion height, a new musical instrument was rapidly gaining popularity around Europe.

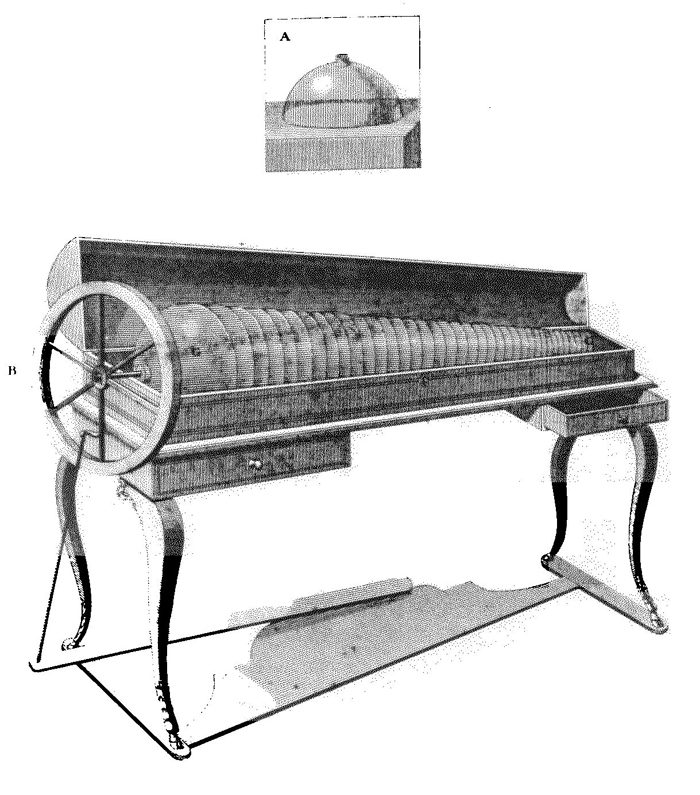

The glass harmonica was beautiful, incredibly impractical, and, for obvious reasons, delicate. Its operation was based on the mechanics of crystal glasses, which produce sound when their rim is lightly rubbed with damp fingers.

In the glass harmonica, the glasses are fitted together in a long row held together by a wooden stick, which is rotated with the help of a pedal.

The first person to write extensively about the glass harmonica was a woman: Anne Ford. In her essay “Instructions for Playing on the Musical Glasses”, she describes the glass harmonica as a revolutionary instrument, especially for women.

According to Ford, women would have greatly benefited from singing along with the sound of the harmonica; in fact, the voice would have been attracted to the pure, transparent sound and would have been contaminated by it by becoming crystalline.

The vitrified voice embedded the woman in a frighteningly angelic and static imagery, perfectly in line with the condition of the ancient woman, encased in bodices of bone, mounded in the layers of her petticoats.

The voice of the ideal feminine is fragile, high-pitched, disembodied, and thus loses fluidity, making the sound material, usually juxtaposed with air or water, something rigid. Rigid, flawless, ready to shatter into painful shards.

Yet, in reality, Franklin’s armonica sounds not at all “disembodied,” for under each note one hears the pull and scrape of a finger stroke against the glass disk. More precisely, one could say that the sound breaks down into two constituent parts, with the scrape “underneath” and the pure sound “above,” as each tone separates into material trace and abstract tone. The vocal effect Ford praises derives from the dramatic difference between the instrument’s upper and lower ranges. The sound becomes increasingly weak and coarse as the pitch descends: the percussive “pulling” or scraping effect grows more pronounced as the pitched sound becomes fainter, and the lowest registers produce muffled tones whose pitch is muted, almost an echo. Only the soprano register escapes the percussive undertone, sounding clear and flutelike. Thus the armonica is not simply “bodiless”; rather it makes audible the process of spirit transcending body, the sublimation of rough, corporealized sound into ideal (feminine) voice.

It is suggestive to think that the transcendence of sound was divided between a bright, shining component and the sound of a scratch.

The action of playing corresponded to a note and a wound, and the two aspects could not be separated because they were generated by the same cause, the same movement. The harmonica summed up the pain and spiritual expectations towards women in a single sound: becoming the mirror of the male soul, lending itself to violent projection.

The harmonica also had the unique characteristic of allowing the musician to hold a pose, to simulate immobility, balance and silence. Visually, the illusion was that women were not really playing, similarly to pictorial representations where one could see their fingers resting on the instruments but without realistically pressing the keys. Hence the instrument managed to reconcile two contradictory desires: to hear the women play and to see them in a graceful, relaxed pose.

Playing is intrinsically connected to a knowledge of the body, to a sensory involvement, and as much as a certain celestial mastery was required of the muse, the fact that her body could be deformed in the breath, or stretched over the keys of a piano was an inappropriate reminder of her humanity.

Moreover, the very structure of the harmonica allowed the beginner to avoid the awkward and clumsy sounds that characterise the early stages of acquiring technical competence.

The male desire was bewildered when faced with the first attempts to play a violin, attempts that generated tremulous and out-of-tune notes, and which could continue for years before becoming attractive. In the case of the harmonica, on the other hand, one only had to touch the rotating crystal and a pure and precise sound was effortlessly generated.

This had an equally significant consequence: the absence of distinction between the amateur musician and the virtuoso.

While other instruments featured the ongoing risk that a musician would become so skilled that she would be enraptured by her own playing and allow herself to be carried away in overly energetic performances, the harmonica guaranteed ‘parlour’ sounds and did not allow any kind of technicality that could be considered unladylike. The musician’s skill was connected more to a calm and spiritual attitude than to bodily competence.

Even the most recognised performers were considered on the basis of the purity they emanated, rather than innovation or expressiveness. Staticity permeated every part of the performance: the sound did not vary in intensity, the body did not move, the soul was calm and relaxed.

In the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the world of the angels is likened to that of the animals. Both are confined to a state of stillness: animals incapable of self-consciousness, angels confined in their apparent perfection.

Men, although at a lower stage of spiritual evolution than angelic beings, are closer to the Absolute because they are endowed with the possibility of change.

Angels are considered bestial precisely because they cannot realise that there is something more than perfection. They will never reach that blissful Nothingness that awaits the enlightened men. Trapped in their own perfection, they are condemned to a limbo full of grace.

No wonder, then, that women are given the most atrocious gift: angelicity, understood as the ‘impossibility of expression and mutation, of even being a shadow’.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the other reason women were associated with the glass harmonica was a substance called ‘animal magnetism’.

Animal magnetism was a theory of the German physician Franz Mesmer, who claimed that illnesses were generated by blockages in a vital fluid that responded to the same laws of electromagnetic attraction that could be observed in magnets. Unlike magnets, however, this fluid did not respond to the effects of magnetic fields, but to other “bodies”.

Basically during treatment the patients would fall into a ‘magnetic sleep’ during which Dr Mesmer would make gestures that would alter the flow of animal magnetism, bringing it back to a harmonious state. Initially he used various instruments to channel his magnetism: ropes, metal rods, pieces of wood and magnets, only to realise that his hands were enough. Like an orchestra conductor, he directed the patients’ vital flow from afar.

“ He did not have to use the body or appeal to the rational mind, but rather manipulated the ether visible current said to circulate through and around all living things. Harmonica’s sound was a perfect analogy for these “waves” of animal mag which were also invisible, perceptible, penetrating, and hard to resist”

The harmonica played a prominent role in Mesmeric séances and sessions, as the instrument seemed to speak directly to the soul, without the mediation of ‘relational’ elements such as words, musical notation or conscious creative work (indeed, Mesmer claimed to produce his most powerful effects when improvising with the harmonica). Entering his studio must have been an evocative experience: in the centre of the living room was a huge pool of clear, still water, and the celestial sound of the glass harmonica was omnipresent, at all hours of day and night.

The feminine sensitivity was suitable to being stirred by the sound of glass, which was said to have healing effects on the nervous system, and to facilitate the mesmeric healing operation. But that same association with the feminine, which made the harmonica famous, became a source of scorn for the next generation.

Wasn’t sensitivity dangerously close to frailty of nerves? To madness? Not in the more dignified sense reserved for artists and thinkers who collapsed under the weight of their own genius, but as instability due to a lack of strength of spirit. The harmonica began to be disregarded for the same reasons it had long been admired: the instrument sounded too ‘young’, immature because of its lack of low register. Coleridge also complained about the timbre, which affected the emotionality so much that it prevented the intellect from concentrating on harmony and composition.

The harmonica followed Mesmer’s descent in popularity, increasingly ridiculed for his unscientific techniques, and ended its parable with a sullied reputation: from being an allegory of purity and perfection, it became the instrument of madness.

Donizetti went so far as to compose a scene from Lucia di Lammermore entrusting the harmonica with the representation of madness:

The autograph score shows that Donizetti first conceived the scene with an offstage armonica accompanying the deranged Lucia as she enters the hall after the murder of her unwelcome husband. The spectacle of the dishevelled and distracted girl in her trance state, seeing visions and attuned to otherworldly voices, recalls earlier scenes of Mesmeric “crisis.” Crossing the literal threshold into the hall, she hovers on the border between waking and trance, between sanity and delirium, even between life and death. The otherworldly tones make a sort of nimbus around Lucia, insulating her from the shock and pity of the crowd. The armonica’s dolce suono first reminds her of Edgardo’s voice and then supplies the armonia celeste of her wedding hymn. Singing a private song, guided by an ethereal orchestra that only she can hear, Lucia enters into an altered state where reality cannot follow

The latest revenge of the glass harmonica was being in the background of a crime at the hands of one unhappy wife.

In her book ‘Female Aggression’, Marina Valcarenghi explains with great clarity the impact of suppressing aggression on the female psyche. The (apparent) absence of that vital force, essential for self-realisation, becomes illness, confusion, depression. Sometimes it is replaced by compensations: superficial manifestations of anger, devouring maternal feelings, narcissism.

Tragically, analysis often considers this psychic imbalance not as the result of systemic violence but as a natural state of the female mind, more inclined to care, gentleness, passivity and above all to putting others before oneself. (I must have said “I love her more than myself” at least once).

At one point in the book in particular I paused, struck by a profound resonance.

Valcarenghi describes an encounter with a woman suffering from psychosis, which made her absolutely certain that she was conversing with Leonardo Da Vinci.

“What did you talk about?”

“About the search for the meaning of life, about art, politics, God, world peace, the important things.”

“You have a particular fondness for Leonardo?”

“I would say yes, and boundless admiration because he is multifaceted, he flies high, he thinks about important things.”

“You were telling me that you had met him other times too?”

“Yes, one other time and he was dressed in a very extraordinary way: he had a white cloak embroidered with gold geometric designs, a blue and white damask jacket suit and a red and purple turban with embroidery; on the table in front of him there were compasses, pencils, papers, drawings, and also strange objects of incredible beauty.”

“You often happen to talk about the meaning of life, world peace…”

“No, precisely,” he interrupted me, “practically with no one.”

The analyst approaches the psychosis without any judgement, evaluating it as psychic reality, and soon realises that she is dealing with a very talented girl, confined to a life that her family and her boyfriend had planned for her, and to which she had sadly adapted.

(What a relief, and what a pain, to be nothing).

She always wore blue.

“I like it and then I seem to be seen less”.

“Why don’t you want to be seen?”

“I feel like there is very little to be seen”.

In the course of the analysis the girl gets back on track with herself, chooses a job compatible with her passions, becomes independent, and slowly the psychosis disappears.

During one of the last sessions the patient asks what her fate will be, and the answer she is offered is significant:

Before we parted, she asked me if she could ever relapse into the crisis, as she used to call it.

“There is this possibility, you are like a crystal glass, precious and thin, but also delicate. You will have to take care of yourself by always being attentive to the life you lead, to the meaning of your days, without becoming lazy and giving in to unimportant things. Then all will be well. Madness is only pain, Giovanna, you must not be afraid of it any more, because now you know how to recognise it and how to deal with it without hiding behind the crisis any longer.”

After a few days, a drawing of a very elegant chalice arrived in the mail, in the background of the paper one could see pencil marks, vague and blurred, like fragments of broken glass.

Underneath it was written: self-portrait.

I wonder if a woman with a soul so strong to produce visions in order to be heard, could really be a crystal glass. If she had been able to endure the life they had planned for her, would she have been stronger, less crystalline?

But more than that, I was struck by the relief that the last statement brings: madness is only pain.

Finally.

What to do with this constellation of anger, pain and madness?

For centuries, drawing one’s own contours, having a shape, could be transformed into having boundaries. Boundaries like the bogeyman of a hospital room, of the status of a shut-in, or of a woman abandoned and therefore destitute.

While reading the book passages, I had the feeling that an amorphous, murky heap was created in her psyche where her identity should have been; a heap as consistent as lava but deprived of its warmth. I thought back to an article about a recent discovery at Herculaneum, where a body whose brain had turned to glass was found. Beautiful to look at, it’s made of shiny black fragments that still retain the dynamism of a material that was once organic. The glass of the skull contained proteins and fatty acids which are common in the brain, as well as fatty acids typically found in the oily secretions of human hair.

“This tissue turned into glass must have been created by vitrification, a process in which a material heats up until it liquefies and then cools very quickly to become glass instead of a normal solid. (…)It appears that this temperature was sufficient to ignite body fat, vaporise soft tissue and melt brain tissue. The brain matter then suddenly extinguished, but Petrone (the archaeologist nda) says that what allowed this to happen currently remains a mystery.”

Woman’s mind, glass mind.

Not a psyche more shatterable than the male one, but stiffened by a forgotten heat that is too strong, unbearable.

Another article, discussing the discovery at Herculaneum, comments: “It is the human body that becomes a witness again, through its own destruction, of a sequence of events, like an archive.”

What violent process does glass make itself the archive of in women’s minds?

My process of vitrification has been a long one, I cannot even say when it began.

Perhaps I too swallowed a glass piano as a child, like Princess Alexandra.

Illness turned my body into glass, some man vitrified my words, and my heart became glass along with my music.

But music has been my way of realising this, of marvelling at my transparency.

I started singing late in life, after a multidisciplinary journey between film and performing arts.

After a long technical training, I was faced with the need for an expressive valve. Rather than in front of me, the need was on the back of my neck, breathing down my neck to force me into action.

It was precisely at that time that I had started attending an improvisation collective, potentially the best place to experiment. Instead, when I gathered enough courage to try to fit in, I always found myself emitting murmurs, whispers, and sonorous breaths. Sometimes I would allow myself an inhale similar to a creak, a small noise.

The circumstances were dominated by a very distressing and judgmental male presence, and my fear of occupying sonic space turned into a stylistic choice.

The sonic breath was to me what blue was to Giovanna .

“I like it and then I feel like I can be seen less”.

My sounds were as fragile as glass, and like glass they tended to become as transparent as possible to what was around them.

Yet I could have done anything.

I often wondered if that space of freedom was only apparent, but trusting my intuition would have meant discovering a state of strength I was not yet prepared for. It was life that gently removed me from those circumstances, without me having to acknowledge the validity of my perceptions.

Once alone, I was left with my transparent sounds, and I did not know how to give them a body.

The instructions to disappear seemed to be everywhere, scattered like clues or crumbs of breadcrumbs throughout my life, while those to reappear were given to me by no one. Sometimes I wondered if my search made sense, or if there were women condemned to be made of glass.

Every now and then I seemed to notice women friends, bent over like me, searching for something. And inside I hoped they were crumbs of reappearance.

Shortly afterwards, I started improvising again, but this time together with Janneke Van Der Putten, a vocal and visual artist and expert in extended vocal techniques. Our friendship guided our meetings, which for months took the form of exchanges of techniques and body practices we had learnt on our ways.

Initially I sang using small sounds, sighs, long notes that blended with the environment around us.

I tried to listen to the resonance of the walls and let my singing be the singing of the walls. I had nothing of myself to judge, for in singing I became landscape.

For the first time, however, my crystal singing had become heavy, fatigued like a dam trying to dam a river in flood. I would have liked to offer her something truer, more my own.

Embarrassed by my singing that was too empty of me, at one meeting I let out my crunch. There and then nothing much happened and I returned to my usual chameleon-like notes. The next day, however, during rehearsals Janneke suggested I go into the dark closet of my house. There, in complete darkness, she began to make that rough ‘my’ sound, inviting me to dialogue. In the blackness and warmth of the small space, the sensation was one of catharsis and relaxation at the same time, because the noise we produced rested gently on my breath.

Years ago, my grandfather gave me an extremely old object, a memento of the years he had spent working in a museum.

It is a Roman tear-gatherer, also called a lacrimatoio.

The lacrimatoio is made of glass, and has a thin, elongated shape that ends in a slight bulge at the bottom, where the tears accumulate. The tear collector itself resembles a tear, in shape and transparency.

In ancient times, the purpose of tear collectors was to collect tears before burial to accompany the dead person to the grave as a testimony to the grief they had left behind. In the 19th century, tear-collectors were back in fashion, and were used to establish the duration of mourning for widows: the tears were collected in small bottles with special stoppers that allowed even minimal evaporation of the liquid so that, when the widow had cried all her tears and they had evaporated completely, the time of mourning was considered over.

A very strange hourglass of grief.

The glass of my tear-gatherer is thick, dense and opaque, and as I renew my wonder at the ancient aura it emanates, I ask him if glass has ever existed without melancholy. He replies that tears are destined to evaporate.

At the end of my time of sorrow, the glass was still there, but it had returned to being obsidian.

Obsidian is the first glass, the only glass that nature itself produces. Obsidian is amorphous, hard material, containing only the memory of what was once magmatic heat.

Perhaps in a way I was right, women’s minds may have an affinity with the shiny black remnants found at Herculaneum.

That mass I had glimpsed reading Valcarenghi’s book was nothing but obsidian.

The obsidian of prehistoric blades, of the modern scalpel.

There it is, the lost aggression, etching, opening, investigating.

Even the glass of my voice has turned into black obsidian.

The crackling over time has taken on more and more body, and has become a guttural, extremely low song, similar to a growl or a roar.

Listening to it, I hear a rough noise in it, like a light percussion of the glottis, and a component of air, tinged by the colour of the vowels.

The sonorous breath is not so distant.

But similarly to the way one obtains the sharp splinters of obsidian through percussion, in the same way I fragment the breath with the glottis, making it wounding and dangerous.

Noise for me is not venting, but a real new voice, which makes my teeth vibrate, and which occasionally frightens those who hear it.

Internally it is still a game of breaths, but thanks to another woman I now know how to inhabit those breaths.

In time I became certain that the women bent over looking, were searching for crumbs of themselves.

Some desperately, some unnoticed.

I believe that for each of us this search involves a different path, a different material, but I am certain that if disappearance is a singular act, reappearance is a collective act.

Diana Lola Posani (Milan, 1994) is a sound artist, independent curator and Deep Listening facilitator based in Naples, Italy. With a background as a performer/performance director, Diana Lola works in the marginal area between performative arts and music. Her interest is the interconnection between listening practices and the development of the voice, which she is specializing through the Vocal Functionality method at Voce Mea by Maria Silvia Roveri, Italy. She is also the founder and curator of Akrida – Sound art festival, featuring international woman-identifying and non-binary artists.

Diana Lola writes, among others, for the journal “A Row of Trees” run by the Sonic Art Research Unit (SARU) – Oxford Brookes University.

In June 2022 she debuted the podcast “Kaikokaipuu” on Fango Radio.

Currently she is interested in working on the common space between sound and poetic imagery, through interdisciplinary pieces and sound poems.