MARTINA MACCIANTI: ART, SOUND, QUEERNESS (1/2)

ZUIHITSU

QUIRKY THOUGHTS COLLECTION

Essays, personal stories and curiosities from our guest fem人le contributors

MARTINA MACCIANTI: ART, SOUND, QUEERNESS (1/2)

A reflection on social transformation through art practice and listening

«Listening is a political act. More precisely, it is an eco-political form of resistance. […] Its inherent eco-political force lies in being the source of the realization – on the basis of ethical principles – of a society based on constructive and collaborative interactions, as well as having a profound meaning of resistance against hierarchical structures and systems of oppression and sensory manipulation. A better future is a more conscious future: listening is the intermediate stage that enables its implementation.»

Daniela Gentile, L’elettronica è donna

(Claudia Attimonelli, Caterina Tomeo)

«I work in between the cracks.»

Meredith Monk

A feminist reinterpretation of events: from Hildegard von Bingen to the Tarantolate*

The term queer/queerness has the powerful meaning of different, non-horizontal, transversal. Queer art practices challenge gender norms and social expectations, creating spaces for the exploration of fluid identities, unconventional relationships, and forms of political resistance. A queer approach rejects by definition the uniquely binary understanding of things. Art and sound thus become vehicles for liberation and affirmation, in which the voices of women and marginalized communities can finally be heard.

Hildegard von Bingen was a German nun, mystic, composer, writer, theologian and philosopher who lived between the 12th and 13th centuries. She was an extraordinary figure, not only for her intellectual and artistic prowess, but also for her role as a woman at a time when women were confined to the role of angels of the house. Active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and as a medical writer and practitioner, she even wrote about the menstrual cycle and female pleasure, despite the constraints of those times.

Music-wise she brought technical and stylistic innovations to sacred music, and wrote lyrics in vernacular languages such as German rather than Latin, that was commonly used for sacred music; she made music more accessible and understandable to audiences and opened it up to listening. Hildegard von Bingen’s influence on religious music goes beyond her stylistic contributions though. Her music was an expression of her spiritual vision, which she sought to convey through beauty and harmony. Her approach to composition was related to spirituality, using music as a means of connecting with the divine, and elevating the human soul and enabling change.

«Either by the form and quality of the instruments or by the meaning of the accompanying words, those listening could be instructed… in inner things.» **

For a long time, women have been excluded from knowledge, therefore whenever they approached it, they did it in a very personal, creative, transversal and non-horizontal way, creating the necessary experience by and for themselves. Hildegard’s almost bizarre approach to knowledge, for example, gave rise to transverse and queer artistic expressions that challenged conventions and broadened horizons.

Starting from this approach, we can reread countless events of the past, such as, for example, the connection between women and drums, an instrument that has deep roots in popular culture and spirituality, which has always represented a connection between women and divinities. This vital and healing connection has survived on the shores of the Mediterranean: think of the phenomenon of Tarantism studied in depth by Ernesto De Martino. ***

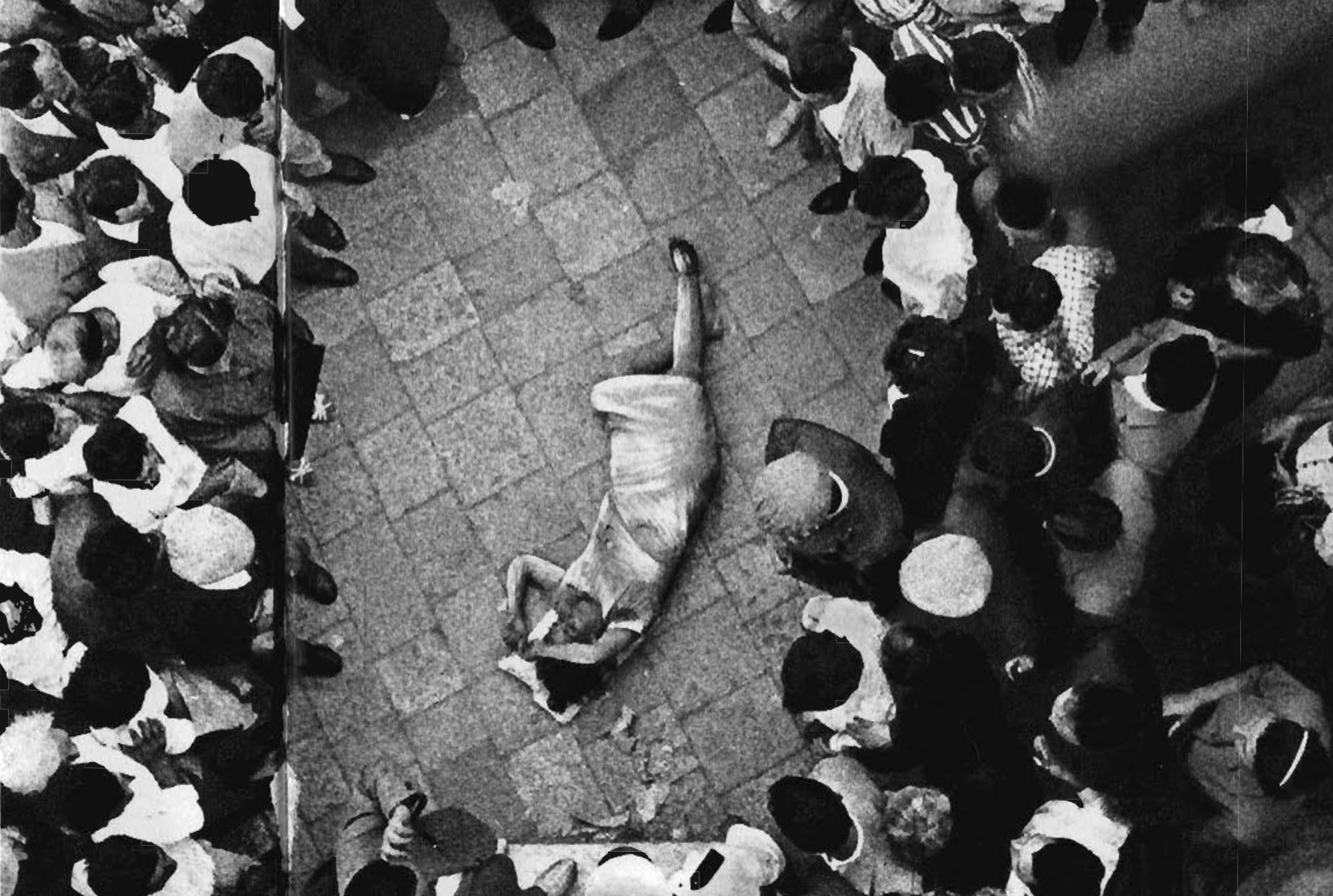

Tarantism, a cultural and social phenomenon rooted in the traditions of southern Italy, is based on the belief that the bite of the tarantula leads to a state of trance and possession, curable only through ecstatic dance and the sound of the drums. This practice, for centuries considered a manifestation of female hysteria, could actually conceal a profound cultural revolution and a message of female emancipation, by rereading it through other lenses, and other utopias.

What if this was just one example of how women found ways to express themselves and find themselves outside of stifling dominant cultural obligations in non-ordinary ways? What if through drumming and ecstatic dance, women could tap into ancestral and spiritual power, challenging social hierarchies and gender expectations? A liberation beyond spider venom.

In a historical context in which women were often relegated to subordinate and silenced roles, Tarantism may have been a vehicle for emancipation and assertion of identity. The taranta dance, with its hypnotic and frenetic rhythm, would thus have allowed women to express their individuality and escape, at least temporarily, from the rigidity of social conventions.

Through drumming and wild dancing, women would have been able to reconnect with an ancestral and spiritual power, defying social hierarchies and gender expectations. The taranta thus became a symbol of a primordial force, capable of shaking the very foundations of a patriarchal and oppressive society.

The trance induced by the dance would thus not be a symptom of hysteria or madness, but rather a way to free oneself from the invisible chains that imprisoned body and soul. A kind of catharsis, in which people could find themselves and access an otherwise inaccessible dimension.

Photo from Ernesto De Martino, La terra del rimorso, Il Saggiatore, 1961

From a utopian and provocative perspective, Tarantism can thus be reinterpreted here as a phenomenon of female emancipation, in which dance and rhythm become tools of struggle and resistance against the oppressions and injustices of the world. From curated hysteria, to the ability to find alternative and creative ways to assert one’s identity beyond cultural and social barriers.

«Rhythmic music seems to have been especially important in rituals associated with ancient goddesses. In the earliest cultures, rhythm was revered as the structuring force of life-so much so that historian William H. McNeill suggests that “learning to move and use the voice [rhythmically], and the strengthening of the emotional bonds associated with this mode of behavior, were fundamental prerequisites for the appearance of humanity” […] The beating of the frame drum of the priestesses articulated this process of creation, bringing into being a link between individual rhythm and that of the community, the environment and the cosmos.» ****

Studies and research on the phenomenon of Tarantism are not lacking, having been studied by anthropologists, ethnomusicologists and historians. What I want to propose is a feminist and cross-sectional look at the phenomenon in order to understand its potential significance and its impact on women in the context in which it developed.

In a patriarchal society that relegated them to subordinate and marginal roles, women had few opportunities to express themselves freely and escape the traditional roles that were imposed on them.The figure of the tarantulas can be interpreted as a symbol of female resistance and rebellion against the social and cultural constraints that oppressed them.

Through dance and listening, the tarantolate found a space and context in which they could express their individuality and use their bodies, without being judged or condemned. Sound and movement became mediums for an act of liberation and affirmation.

Cracks, political possibilities, reality, and listening

Sound and image became tools to explore and understand the plurality of human experiences, and to highlight possible inequalities and asymmetries underlying the official narratives of history and politics. The political possibilities of art^^ (in all its forms and expressions) are multiple and include the creation of new truths and new articulations of meaning, which challenge dominant narratives and open spaces for the voice and expression of marginalized communities and bodies. Art’s power to reveal the complexity and plurality of the world invites us to recognize the importance of diversity and work to build bridges between differences, rather than erect walls of separation and inequality: it warns us against the conventional orientation that often leads us to view the world in a limited and one-dimensional way. As Salomé Voegelin writes in her essay The political possibility of sound: “I aim to position sound and listening as generative and innovative intensities in the space of the political in order to probe their potential for an exploration of politics and to try their capacity to imagine and effect its transformation into plurality without opposites.”

It is a matter of language and perspective: a perceptual shift in what we see, encounter, and feel is needed as well as a change from a monolithic view of diversity to a three-dimensional creation of plural possibilities.

Throughout history many women artists have experimented with new forms of expression and created works that challenge the boundaries between art and life, male and female, sacred and profane. I immediately think of avant-gardists such as composer Pauline Oliveros, who found innovative ways to explore issues of identity, sexuality, and power, creating a body of work that continues to influence and inspire subsequent generations.

Pauline Oliveros has left an indelible mark on the history of sound art through her ability to explore complex issues through sound, finding innovative ways to explore the relationship between sound and identity, creating works that invite listeners to reflect on their own sound experience and the nuances of their identity. Through her artistic practice, she has challenged cultural norms and conventions that often limit the expression of women and marginalized communities, opening spaces for the voice and expression of voices that often remain ignored or removed from collective memory. She founded the Deep Listening Institute, an organization that promotes the practice of deep listening as a tool for social and cultural transformation, and has collaborated with numerous artists and musicians to create collective works and engage audiences in the practice of active listening.

Why are these perspectives important for feminist struggle? Because interdisciplinary artistic collaboration is a practice that can bring significant outcomes, both artistically and socially: working with people from different fields of study, different life experiences, different social positioning, can enrich the creative process and offer new perspectives on the world, on reality as we know it.

To place ourselves in a position of absolute, attentive listening is what we should do in implementing feminism; to develop an ability for deep listening, analysis and introspection, to understand/see/feel beyond. ^^^

«Deep Listening is listening to everything all the time, and reminding yourself when you’re not. But going below the surface too, it’s an active process. It’s not passive. I mean hearing is passive in that soundwaves hinge upon the eardrum. You can do both. You can focus and be receptive to your surroundings. If you’re tuned out, then you’re not in contact with your surroundings. You have to process what you hear. Hearing and listening are not the same thing.» ^^^^

The heritage Pauline Oliveros left us goes beyond the musical sphere because she broke new ground in queer feminism. Through creating visible forms of queer feminist expression, she provided a model for other queer people to follow in her footsteps. Oliveros has made the personal political and pushed the boundaries of what it means to be a composer. Her work is a significant testament to the importance of diversity and plurality of voices in culture and society, which we must listen to, understand, and make our own.

What we need to rediscover and bring to our relationships processes and to the feminist struggle is a deep ability to listen to and understand experiences far from our own; and the adoption of a transversal and open approach to the world, we need to adopt a transversal and open approach to the world that will enable achievements that a monolithic and horizontal vision will not allow. Human and social relationships are built on the ability for encounter and listening going far beyond feeling. We must learn to embrace plural perspectives, which often seem distant and selfishly incomprehensible to us, because only then can we broaden our understanding, build deeper relationships and make the struggle for rights more effective and inclusive. A rigid approach that is incapable of listening to what is different can never lead us to our destination.

Pauline Oliveros, the Fort Worden Cistern, 1988 (© Brooklyn College)

«SUONARE LA CITT à

(SOUNDING THE CIT Y)

SIGNIFICA

(MEANS)

CHE UN GIORNO LONTANO

(THAT ONE DAY FAR AWAY)

QUANDO VEDREMO UN UOMO

(WHEN WE’LL SEE A MAN)

GIOCARE CON UN LUNGO BASTONE

(PLAYING WITH A LONG STICK)

ATTRAVERSO

(THROUGH)

UNA CANCELLATA

(A RAILING)

E LO SENTIREMO FARE CON GLI ELEMENTI PARALLELI

(AND WE WILL HEAR HIM DOING WITH THE PARALLEL ELEMENTS)

DELLA CANCELLATA

(OF THE RAILING)

DELLE LINEE TRATTEGGIATE DI RUMORE

(A FEW DOTTED LINES OF NOISE)

Pi ù

(MOR E)

FITTE

(FREQUENT)

O

(OR)

MENO

(LESS)

FITTE

(FREQUENT)

NON VEDREMO UN POLIZIOTTO

(WE WILL NOT SEE A POLICEMAN)

ARRESTARLO

(ARREST HIM)

PERCH é

(BECAUS E)

DISTURBAVA L O R D I N E

(HE WAS DISTURBING T H E O R D E R).

ma passeremo senza badarci

(but we’ll pass by without caring)

e al bambino che ci chiederà qualcosa

(and to the child who asks us something)

risponderemo

(we’ll answer)

vedi quello suona la cancellata

(see that one who is playing the railing)

da grande lo saprai fare anche tu

(when you grow up you will know how to do it too.)» “””

* Tarantolate refers to people who are the subject of this practice, phenomenon explored further in the text.

** Hidegard Von Binden in a letter to Magonza’s prelates

*** Ernesto De Martino, La terra del rimorso, Il Saggiatore, 1961

**** Layne Redmond, Quando le donne suonavano i tamburi, Venexia, 2021

^^ Salomé Voegelin is a Swiss artist and sound theorist who has developed the concept of the “political possibility of sound,” an approach that seeks to explore the political and social potential of sound as an artistic medium. The Political Possibility of Sound: Fragments of Listening, 2018, Bloomsbury Academic; Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art, 2010, Continuum International Publishing Group

^^^ The focus here is on Western feminism (what we know in the narrative as white feminism) that has left out this very pillar in its doing, deep listening, not including voices, excluding bodies from its moving forward.

^^^^ Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice, iUniverse, 2005

“”” Excerpt from ‘Suonare la città’ (1969), Il metodo per suonare, Giuseppe Chiari, Martano editore, 1976

Martina Maccianti, born in 1992, lives in Florence and writes about feminism moving through multiple and traverse lines. She is the founder of Fucina, an online space that focuses on topics such as sexuality, rights, equality, ecology, passing whenever possible through art and music. Martina sees in a feminism that is aware of the different and plural oppressions that can act, the only point of solution for a society that does not give the same space to every person, to everybody..