MARTINA MACCIANTI: ART & (IS) POLITICS

ZUIHITSU

QUIRKY THOUGHTS COLLECTION

Essays, personal stories and curiosities from our guest fem人le contributors

MARTINA MACCIANTI: ART & (IS) POLITICS

Demetrio Paparoni, critic and curator, in agreement with the artist Ai Weiwei states that ‘there is no such thing as disengaged art: there are activists who do politics through art’; art is therefore always political for them. But is it? Is it enough for art to exist to inherently have a political and social value – and impact?

Art can be political, but it is not so by nature, only by manifesting itself.

The politics of art (or in art), for example, is essential to make visible the realities that often remain on the fringe of attention of the society in which we live. What art does have, of course, is the power to create spaces for reflection and awareness-raising, to highlight inequalities and to prompt concrete actions for social change. In particular, art policy should focus on enhancing the potential for mediation and visibility of so-called marginalities, i.e. those communities and realities that are often ignored.

The empowerment of these margins is, in fact, essential for the construction of a fairer and more equitable society, where all people have the same opportunities and rights.

(1) Nadine Faraj; Joyce Yahouda Gallery, Montreal, presents “The Whole World Has Gone Joyously Mad”

When we talk about art and politics today, we are talking about something that goes beyond a simplistic question of political orientation, but rather of political emancipation. Art must not only be an aesthetic or entertainment product, but it must utilise the power it has to address social and political issues, to stimulate public debate and to create, propose, imagine real change. Art politics can play a crucial role in this process, opening up new spaces for expression and participation. The artistic act must focus on enhancing the political potential of art itself, supporting the production and enjoyment of works that bring with them relevant social and political issues and, above all, guaranteeing access to art for all, and the understanding of art by all, so that it can be a means of democratic and widespread expression and participation.

Art can be used as a tool for protest and social criticism, to denounce injustice. To promote a culture of equality and freedom. To propose new worlds. To activate new interactions. To imagine new methods.

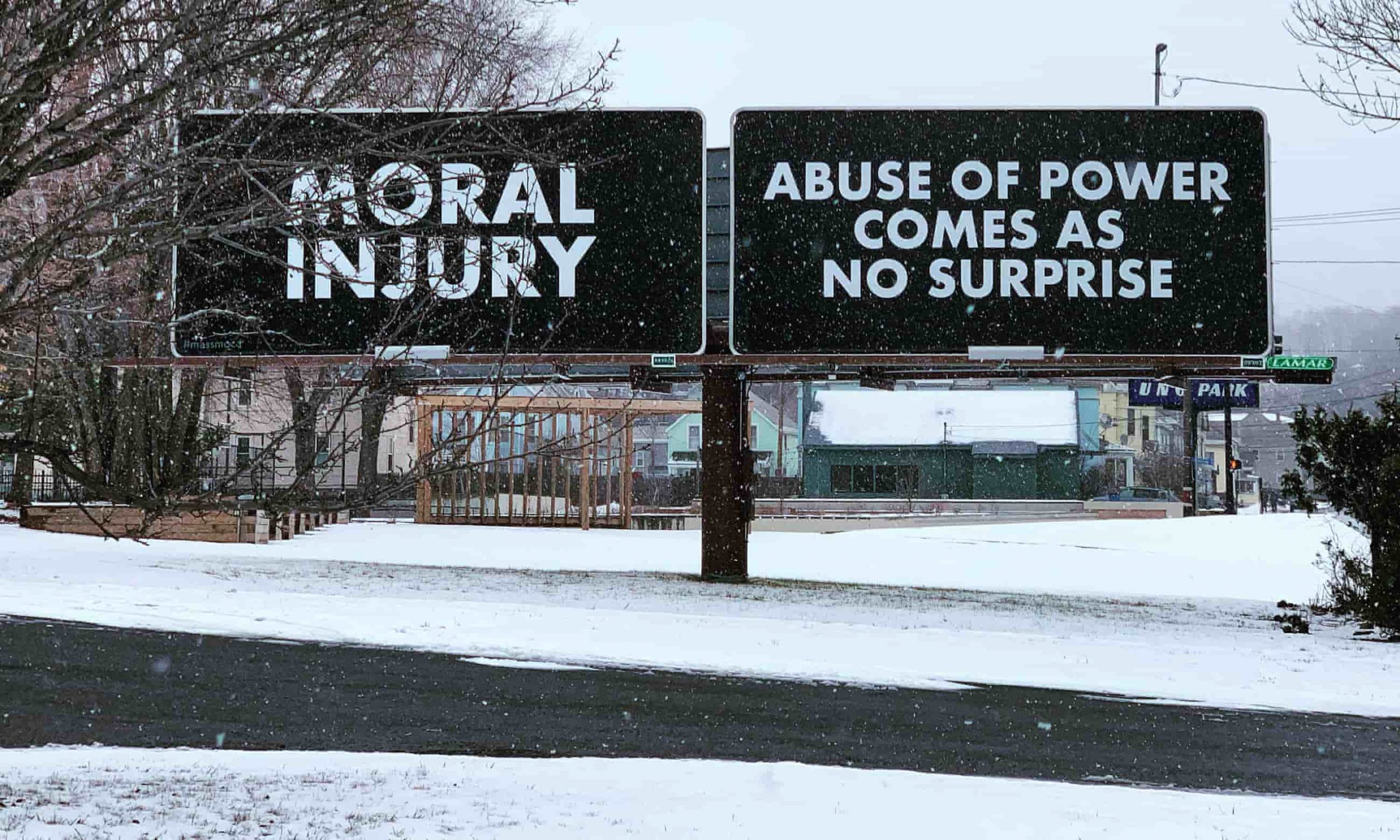

(2) Jenny Holzer, ”Abuse of Power Comes As No Surprise and Moral Injury”, North Adams Massachusetts in January 2021, ph: sep120/Stockimo/Alamy

In this process, it is vital to support access to art for all, without discrimination of gender, social class, ethnicity or sexual orientation, so as to ensure that the voices of the margins are heard and that art can play its role as an engine for social change.

“Painting,” said Pablo Picasso, “is not meant to decorate flats.

It is an instrument of offensive and defensive warfare

against the enemy.”

Let me add to Picasso’s words that Art can and must be a bulwark of care and collectivity. A source of empathy and union, in the face of an abstract enemy that wants us disunited, wants us unique singularities.

“Now art begins to merge with the therapeutic act

of reactivating sensitivity.”*

* Franco Bifo Berardi, 2012, ‘Perché gli artisti? MACAO è la risposta’, Sinistrainrete

(3) Lydia Ourahmane, The Third Choir (2014), Manifesta 12, Palermo

I believe that we need an art that is not content to be mere decoration or entertainment for aesthetics, but rather aims to investigate and analyze the historical, political and cultural context in which it finds itself. Only in this way can art become a tool to provoke revolution, to bring forth new identities, new subjectivities, capable of challenging the established order and opening up new horizons.

Art must be able to enable worlds and subjectivities that would otherwise remain unexplored.

Art must be able to dialogue with reality and question itself about it, not merely reproduce it passively. Only in this way can art become an instrument of liberation and change, capable of creating a new time of revolution.

The artist has the power, through the transmediality at their disposal, to concretise a narrative, an imagery that denounces and represents society, the historical period in which it moves, the dominant society, and to draw from it a tangible manifesto that becomes a critique and a proposal at the same time.

The artist subverts the space she/he lives in.

Imagine new realities. Destructure the existing one.

Let her/him become the embodiment of a new that is collective and diffuse.

1 Nadine Faraj makes watercolour paintings with raunchiness, humor, tenderness and soul. She paints portraits and sexualized figures in varying degrees of abstraction often drawn from the worlds of pornography and erotica. Her fluid style allows her figures to emerge as deeply psychological and emotional beings, with a full sense of their humanity.

Not long ago, while Nadine and I were chatting remotely, there was a sentence she said that I think encompasses everything I shared in this article: “Art is the field where we can explore complex ideas; art can help us metabolising challenging realities […] our society continues to carry out daily acts of domination and degradation, however art has the ability to to take to a different level, a deeper one”.

2 Jenny Holzer is one of the most famous North American conceptual artists . She is a member of New York ARS (Artists Rights Society) and she has pionereed the use of writing as an art medium. The declaration which is object of the work “ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE” is part of her series Truisms: in the most recent years this series has become more reactive to world events and has more than ever resonated with political significance.

3 Lydia Ourahmane was born in Saïda, Algeria, in 1992. She currently lives in London and works in the UK and in Algeria. Her art crosses new media, video, performance, sculpture, and found objects, thus exploring transitory forms of existence and resistance and observing compounds of surveillance and social/political structures. ‘The third choir’ is made up of 20 empty barrels of Naftal oil, at the bottom of which an equal number of mobile phones are set on the same FM frequency, reproducing the noise of a monotonous industrial atmosphere. Such objects in space manifest questions about their own meaning for the social and political structures in Algeria, about desire coalitions and the disruptions leading to illegal migration. ‘The third choir’ is at the same time a struggle against the suffocating Algerian bureaucracy and a symbolic materialisation of migrations.

Martina Maccianti, born in 1992, lives in Florence and sees art as a powerful means of revolt, weapon, catharsis, expression and finally healing. In addition to her personal artistic work, she has a deep passion for the world of art, whether it be visions or sounds. She is the founder of Fucina, an online space that deals with topics such as sexuality, rights, equality, ecology, passing whenever possible through art and music. Martina Maccianti is first and foremost a feminist, and sees in feminism, which is aware of the different and plural oppressions that can act, the only point of solution for a society that does not give equal space to every person.